Alanna Styer

Issue 158

The National Parks have been an integral part of my personal and familial history. There are photographs of memories I do not have; sitting at a picnic table near a covered wagon and running through the woods of Yellowstone National Park at the tender age of three. My earliest venture into landscape photography happened at Badlands National Park, with a little gold 35mm camera that had only two settings, M and P.

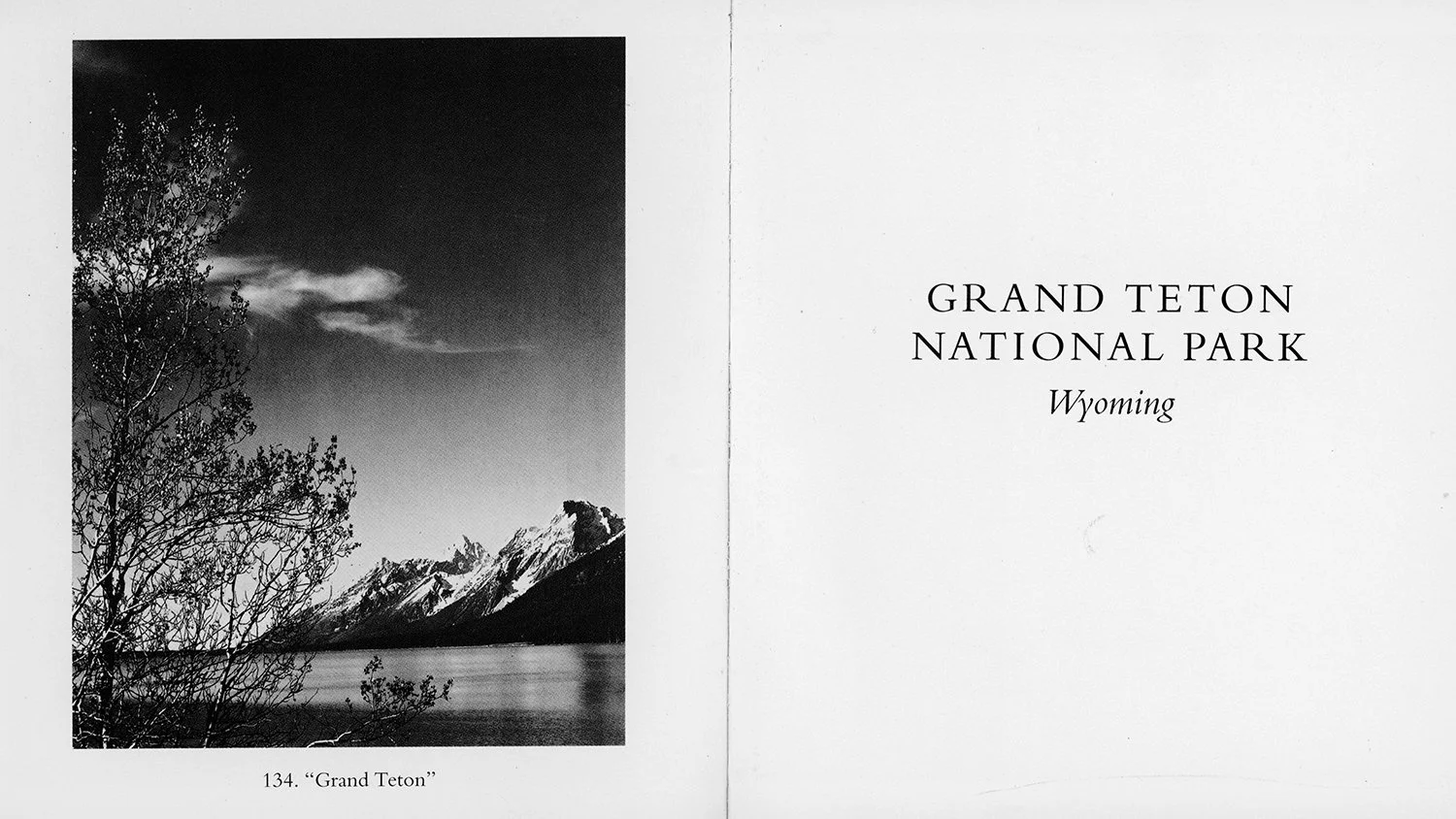

Through family archives, photographs and a little humor I am exploring my relationship and history with the National Parks. The stories of grandeur my parents wove about their adventures and my early childhood infiltrate my experiences and confuse my memories; I am often uncertain of what memories I have adopted and which are my own. I follow in the footsteps of the photographers before me such as Ansel Adams and my own father, who traveled great distances to get the perfect shot. Not only is this type of ecotourism a tax on our environment, but often these images greenwash history and perpetuate the myth that these lands were saved from ruin by the establishment of the parks service. This is not to say that important and impactful conservation is not being done — it’s just a little more complicated.

In my early 20s I began a quest to visit and photograph all 63 major National Parks in the United States. As I took these trips I was met with information about the history of the National Parks Service, the Civilian Conservation Corps, and how the parks maintain and conserve this land for our enjoyment. Then at Mammoth Cave National Park I heard a new story; one about a multi-generational family of tour guides who began working in the cave as enslaved people and eventually were able to buy land above the caves to live and farm on freely. As the cave system transitioned to a National Park in 1941 these families lost their land and their jobs. This story jolted me out of passive admiration for the National Parks and into a critical look at their founding and continued existence.

Just like this landmass commonly called the North America, the National Parks were not untouched and unpopulated “virgin” lands waiting for someone to find and admire; rather these lands thrived because they were nourished by Indigenous hands, knowledge, and practices. Those native to the lands that are now National Parks, were often killed or forced onto reservations where their knowledge and continued existence has been largely ignored. As I travel through the National Parks it is still rare to hear the stories of genocide and emanent domaine the predated their establishment and turned homes and sacred sites, without tangible borders, into parks with entrance gates, reserved for those that can afford to travel through them.

This project is in progress and yet to be titled.

Alanna Styer (they/she) lives and works on the tradition homeland of the Nung’wu (Southern Paiute People) in the area commonly referred to as Cedar City, Utah

www.alannastyer.com | @a_lot_a_alanna

Untitled

Near Teewinot 2019

Dad (44) & Me (3)

Untitled

Ansel (40) & Me (20)

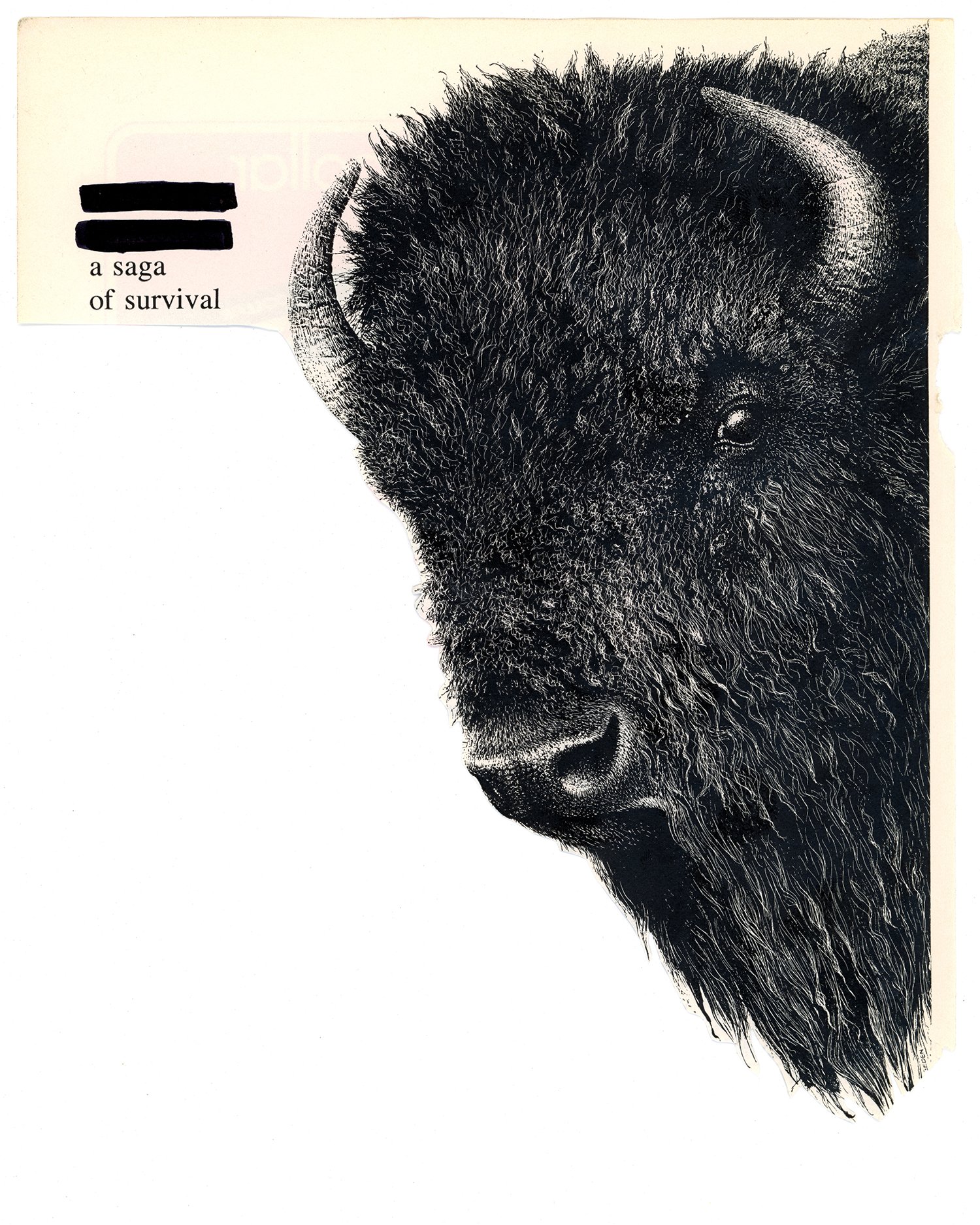

She sat on a bison robe near a geyser and sang. 2019.

National Geographic 1974

After Yellowstone was established, Indigenous peoples were removed and often excluded from its spaces. Today “members of American Indian tribes or traditionally associated groups may enter parks for traditional non-recreational activities without paying an entrance fee.” For recreational related activities entrance fees at Yellowstone begin at $20. 2019.

Images © Alanna Styer